Veere, Tìr Ìosal: Na Dùitsich agus na h-Albannaich

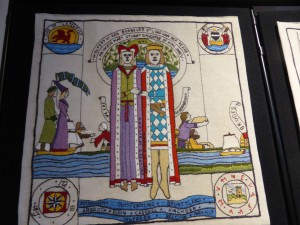

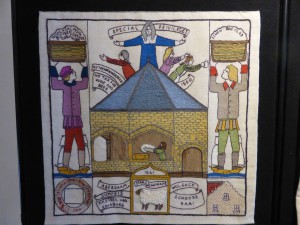

Banais rìoghail – royal wedding

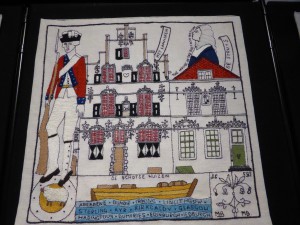

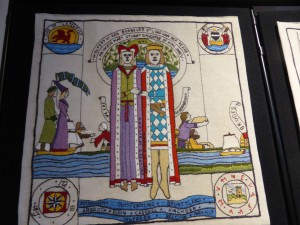

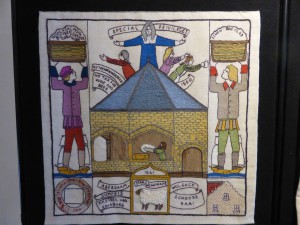

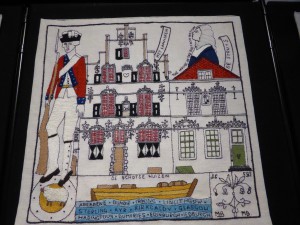

Anns an Iuchar bha mi ann an Veere, baile beag bòidheach ann an Zeeland san Tìr Ìosal, gus Grèis-bhrat Diaspora na h-Alba fhaicinn; bha an taisbeanadh-siubhail mòr an sin fad dà mhìos. Bha mi air pàirt beag dheth fhaicinn ann an Inbhir Nis an-uiridh mar-thà, ach b’ e seo an obair-ghrèis iomlan, barrachd is 300 pannalan tarraingeach. Tha iad air an grèiseadh le coimhearsneachdan-fuaigheil saor-thoilleach air feadh an t-saoghail, ann an Canada, Patagonia, san Ruis, sna h-Innseachan, ann an Astràilia, Sìona, san Roinn Eòrpa … anns gach àite air an t-saoghal far an do leig Albannaich an acair bho na Meadhan-Aoisean a-mach. ‘S e aon de trì “peathraichean” a th’ ann – Grèis-bhrat Blàr Sliabh a’ Chlamhain (2010), Grèis-bhrat Mòr na h-Alba (2012-13) a sgrìobh mi mu dheidhinn an-uiridh, agus Grèis-bhrat an Diaspora (2012-14) e fhèin, gach fear fo stiùireadh neach-ealain Andrew Crummy.

Cha bhi Grèis-bhrat an Diaspora ri fhaicinn ann an Alba a-rithist ro 2017 – tha e a’ siubhal tron t-saoghal san eadar-àm; mar sin bha mi ro thoilichte cothrom fhaighinn fhaicinn ann an Veere. (Ach tha Grèis-bhrat Mòr na h-Alba ri fhaicinn an an Cair Chaladain an-dràsda, gu 20mh den t-Sultain.)

Tha na dealbhan de Ghrèis-bhrat an Diaspora a thog mi ann an Veere rim faicinn an seo, ma bhios ùidh agaibh annta: https://www.flickr.com/gp/seaboard/151th6

Sisteal – Cistern

Ach carson a bha e ann an Veere, anns an Tìr Ìosal, idir? Tha sinn buailteach dìochuimhneachadh gur e an fhìor rathad-mhòr a bha anns a’ mhuir gus o chionn ghoirid, agus mar sin bha e nàdarra gu leòr gun robh ceanglaichean-malairt agus iasgaich làidir ann eadar taobh an Ear na h-Alba agus an Tìr Ìosal. Bha luing Albannach air acair ann an Veere anns an 13mh linn mar-thà, ged a bha Brugge na bu chudromaiche an toiseach, le bathair-a-steach Albannach saor o chìsean. Ann an 1407 fhuair Brugge cùmhnant mar aon phort-inntrigidh dhan Roinn Eòrpa ( ‘staple port’) airson bathair Albannach, le còirichean sònraichte, ach às dèidh dhan abhainn an-sin stopadh le eabar, fhuair Middelburg, baile-malairt ann an Zeeland, an t-sochair seo ann an 1518. Ach bha Middelburg fhèin beagan fad’ air falbh bhon mhuir fhosgailte cuideachd agus mar sin chaidh Veere, port na bu lugha ach glè fhreagarrach – air a’ chosta ach faisg air ionad-malairt mòr Middelburg (agus na bu bhàidheile ri Pròstanaich) ainmeachadh mar ‘staple port’ airson bathair Albannaich ann an 1541, rud a mhair gu 1799.

Bha luchd-malairt Albannach steidhichte ann an Veere fada ro sin, ge-tà. Bha na ceanglaichean cho làidir ‘s gun do phòs a’ Bhana-phrionnsa Màiri, nighean Sheumais 1 Alba, Wolfert à Borselen, Morair Veere, ann an 1444. Thairis air ùine dh’fhàs coimhearsnachd Albannach làidir ann an Veere, aig an robh sochairean sònraichte, mar eaglais agus lagh aca fhèin, tobair mhatha meadhan sa bhaile (mar An Sisteal, ri fhaicinn fhathast), saoradh bho chìsean air fìon is leann, lighiche is ostair aca fhèin, amsaa. Bha Taigh na h-Alba ann airson choinneamhan malairteach agus comannach, agus Gleidheadair (‘Conservator’) mar cheannard na coimhearsnachd Albannach san Òlaind. ‘S e dreachd gu math politigeach a bh’ anns a’ Ghleidheadair uaireannan – m.e. gus luing-cogaidh Bhreatannach a chur air dòigh, no rèisimeid Albannach a thogail, mar dhìon nuair a bha Veere no an Tìr Ìosal ann an cunnart, m.e. an aghaidh nan Frangach no nan Spàinnteach. (Fiù’s san Darna Chogadh ‘s e saighdearean Albannach a shaor Veere, mar phàirt de Ghnìomhachd Infatuate, 1944.)

Cuileann-Ros, Culross

Agus dè am bathar a chaidh a mhalart? Sa phrìomh àite bha a’ chlòimh Albannach, bho na Meadhan-Aoisean, bho thùs rùsgan corralach bho mhanaich Abaid Mhaolrois. Chaidh seo tro Veere (mar ‘staple port’) a-steach dhan Roinn Eòrpa, far an robh margadh prothaideach a’ feitheamh. Ach thar nan linntean dh’fhàs bathar eile cudromach cuideachd, leithid sgadan, bèin, lìon, uisge-beatha, agus gual agus salann gu h-àraidh à Cuileann-Ros ann am Fìobha (baile-cèile Veere an-diugh, agus fianais e fhèin de na linntean-malairt tarbhach sin).

Agus dè chaidh air ais sna luing-mhalairt? Bha bathar gu math eadar-dhealaichte ann, leithid fìnealtasan-bidh is dighe Eòrpach, aodach, leathar, bathar-pràis, taidhleachan Dùitseach. Aig àm a’ Chogadh Chatharra ann am Breatainn, chuir luchd-malairt Dùitseach an t-uabhas de dh’armachd gu Alba. Ach rud ceart cho cudromach, ‘s e na leacagan-phana dearga a thàinig a dh’Alba mar bhallaist agus a tha rim faicinn an-diugh fhahast air mullachan nan taighean taobh an Ear na h-Alba, gu h-àraidh ann am Fìobha – leithid Cuileann-Ros, Dìseart is Cathair Aile.

Leis gun robh ceanglaichean cho maireannach agus seasmhach eadar na coimhearsnachdan Albannach agus Dùitseach, is beag an t-ioghnadh gun robh iomlaid-fhoghlaim sgairteil ann cuideachd, seòrsa de phrògram-Erasmus tràth, le oileanaich Dhùitseach a’ frithealadh oilthighean ann an Alba agus oileanaich (agus ollamhan) Albannach aig Oilthigh Leiden.

De Schotse Huizen

Nuair a chaidh sochairean agus inbhe ‘staple port’ a thoirt air falbh aig àm Napoleon, lùghdaich malairt le Alba (dh’fhàs Rotterdam na bu chudromaiche), agus re ùine chaidh coimhearsnachd nan Albannach ann an Veere às a chèile, às dèidh nan linntean mòra. ‘S e baile sàmhach ann a th’ ann an Veere a-nis, a thaobh malairt co-dhiù (gu h-àraidh nuair chaidh dam a thogail aig beul na linne ann an 1961), le marina beòthail agus meadhan a’ bhaile eachdraidheal bòidheach, làn de chraobhan agus flùraichean, nam measg mòran ròsan-malla brèagha àrda. Ach dè tha air fhàgail de na h-Albannaich ann an Veere an latha an-diugh? Tha fiosrachadh agus cunntasan oifigeil gu leòr ann, agus dealbhan agus buill àirneis a bha aca, cuid dhiubh rim faicinn sna taighean-tasgaidh, ach gu mì-fhòrtanach chan eil mòran de na togalaich aca ann tuilleadh. Ach tha muinntir Veere uabhasach moiteil às an fheadhainn a tha air fhàgail.

A-mach on t-Sisteal, taigh-tobair cloiche às an 16mh linn, tha dà sheann taigh drùidteach ann, faisg air a chidhe, air a bheil De Schotse Huizen, an dà chuid air an togail san 16mh linn cuideachd. Bha sgèimheachadh nan taighean seo a’ nochdadh inbhe an luchd-malairt Albannach. ‘S e Het Lammetje (an t-uan) a th’ air aon dhiubh, fear math ghlèidhte, a’ toirt tarraing air a’ mhailairt-chlòimhe, agus e na dheagh shampall den stoidhle Ghotach Dhùitseach, air an taobh a-muigh ‘s a-staigh. Chaidh am fear eile, In Den Struijsch (an struth) atharrachadh gu ìre ri ùine, ach tha e brèagha fhathast, le eileamaidean clasaigeach air. Tha taigh-tasgaidh inntinneach mu àm nan Albannach anns na taighean an-diugh, agus sin far an deach Grèis-bhrat an Diaspora a thaisbeanadh.

Nach math gu bheil fianais mar sin ann air an dàimh fhada eadar Alba agus an Roinn Eòrpa – bha Alba riamh gu math fosgailte a thaobh cheanglaichean do ar nàbaidhean thall thairis. Faodaidh mi turas gu Veere, Middelburg is Brugge a mholadh – sgìre is bailtean brèagha iad fhèin, agus iad nam pàirt cho inntinneach den eachdraidh againn fhìn.

Veere, NL: the Dutch and the Scots

Margadh – Market, Veere

In July I was in Veere, a small town in Zeeland, the most southerly province of the Netherlands, to see the Scottish Diaspora Tapestry; the travelling exhibition was there for about 2 months. I had already seen a small selection of the panels in Inverness last year, but this was the full works, more than 300 fascinating panels. They were embroidered by volunteer groups all round the world, in Canada, Patagonia, Russia, India, Australia, Europe…everywhere in the world where Scots dropped anchor, from the Middle Ages on. It’s one of three “sisters”: the Prestonpans Tapestry (2010), the Great Tapestry of Scotland (2012-13), which I wrote about last year, and the Diaspora Tapestry itself (2012-14), each one under the artistic diirection of Andrew Crummy.

The Diaspora Tapestry won’t be back in Scotland until 2017 – it’s touring the world in the meantime, so I was delighted to have the chance to see it in Veere. (But the Great Tapestry is on show in Kirkaldy till 20 September.)

My photos of the Diaspora Tapestry can be seen here, if anyone is interested: https://www.flickr.com/gp/seaboard/151th6

But why was the Tapestry in Veere in the first place? Well, we tend to have forgotten altogether that it was the sea which was the real highway until comparatively recently, and that there were therefore close trade and fishing links between the East of Scotland and the Low Countries. Scottish ships were already anchoring in Veere in the 13th century, although Bruges was more important initially, with duty-free imports of Scottish goods. In 1407 Bruges negotiated the contract to be the ‘staple port’ for Scottish imports, i.e. the sole entry-port for Europe, with special rights, but when the river there silted up, Middelburg, a trading centre in nearby Zeeland, was granted that privilege in 1518. Middelburg itself however was also a bit too far from the open sea, and therefore Veere, a smaller but more suitable port right on the coast, close to Middelburg’s commercial hub (and more open to Calvinism), was declared ‘staple port’ for Scottish imports in 1541, a role which lasted till 1799.

An t-Sisteal – Cistern

Scottish merchants had established themselves in Veere long before that, however. The links were so strong that Princess Mary Stewart, daughter of James I of Scotland, married the Lord of Veere, Wolfert van Borselen, in 1444. In the course of time the Scottish community in Veere became very strong, and acquired special rights, such as their own church and courts of law, good wells in the town centre (like the Cistern, still there today), freedom from duties on beer and wine, their own doctor and innkeeper, etc. There was a Scots House for trade and social meetings, and a Conservator as head of the Scottish community in the Netherlands. This could be quite a political role at times, e.g. deploying British warships, or raising Scottish regiments, when Veere or the Netherlands was in danger, e.g from the French or Spanish. (Even in World War II it was Scottish soldiers who liberated Veere, as part of Operation Infatuate in 1944.)

And what kind of goods were traded? Primarily it was Scottish wool, from the Middle Ages on, originally superfluous fleeces from the monks of Melrose Abbey. These were channeled through Veere, as ‘staple port’, for trade in Europe, where a profitable market was waiting. But over the centuries other exports became important too, such as herring, flax, whisky, and especially coal and salt from Culross in Fife (twinned with Veere today, and itself testimony to the prosperous centuries of trading).

Taigh-tasgaidh, museum

And what came back in the merchant ships? There was quite a variety of goods, such as European food and drink specialities, textiles, leather, brass-work, Dutch porcelain tiles. At the time of the Civil War in Britain, vast amounts of weapons were also exported to Scotland by the Dutch. But just as importantly, the red Dutch roof-tiles that were used as ballast in the returning ships (as the holds of coal-ships were too dirty for anything other than building materials) still leave their mark on house-roofs in the East of Scotland today, especially in Fife – for example in Culross, Dysart and Crail.

With such a strong, long-term relationship between the Scots and the Dutch, it’s hardly surprising that there was a lively educational exchange too – a sort of early Erasmus programme, wiih Dutch students attending Scottish universities, and Scottish students (and professors) at Leiden University.

Once Veere’s ‘staple port’ privileges were removed by Napoleon, trade with Scotland decreased (Rotterdam became more important), and over time the centuries-old Scottish community in Veere disintegrated. Veere today is a quiet backwater, as far as trade is concerned (especially since the building of the dam over the mouth of its firth in 1961), but it has a lively marina and a very pretty historic centre, full of trees and flowers, among them beautiful tall hollyhocks. But what is left of the Scots in Veere today? There’s plenty of information and offical records, and paintings and furniture, which you can see in the museums, but unfortunately not too many buildings any more. However the people of Veere are extremely proud of those they do still have.

De Schotse Huizen

Apart from the Cistern, a stone pavillion housing the well dating from the 16th century, there are two impressive old houses beside the quay, called De Schotse Huizen, both built in the 16th century too. The richness of the decoration showed off the status of the Scots merchants in Veere. One of them, a well-preserved example of Dutch Gothic inside and out, is called Het Lammetje (the lamb), referring to the Scottish wool trade. Its neighbour, In den Struijsch (the ostrich) has been altered over the years but is still attractive, with classical elements. There’s an interesting museum about the time of the Scots merchants inside them nowdays, and that’s where the Diaspora Tapestry was displayed.

Isn’t it great that there are still such witnesses to the historic relationship between Scotland and mainland Europe – Scotland was always very open as regards links with our neighbours over the seas. I can certainly recommend a visit to Veere, Middelburg and Bruges – the area and towns beautiful in themselves, and with a long heritage they share with us.

![P1310958[1]](http://www.seaboardgaidhlig.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/P13109581-225x300.jpg)

![P1170826[1]](http://www.seaboardgaidhlig.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/P11708261-300x225.jpg)

![P1060816_zps5f6eab3c[1]](http://www.seaboardgaidhlig.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/P1060816_zps5f6eab3c1-300x225.jpg)