A’ Ghàidhlig ann an Eachdraidh Machair Rois Pàirt 4:

An Darna Cogadh gu ruige seo: Ginealaich na Beurla

Aig àm an Dàrna Cogaidh thàinig Feachdan na Dùthcha dhan sgìre, gu h-àraidh leis na raointean-adhair a chaidh a thogail anns a’ Mhanachainn agus Tairbeart (‘the dromes’). Cuide riutha thàinig mòran bhall-seirbheise agus luchd-obrach à pàirtean eile den Rìoghhachd Aonaichte, agus bhiodh daoine na sgìre ag obair còmhla riutha, m.e. air làraich-thogail no anns na h-ionadan-bìdh (bha fear ann faisg air far a bheil an Seaboard Hall an-diugh). Dh’fhàg mòran daoine òga an sgìre leis na Feachdan cuideachd, na h-iasgairean na b’ òige nam measg. Cha robh a’ Ghàidhlig feumail no freagarrach idir anns a‘ chonaltradh an-sin – agus ‘s ann sean-fhasanta a bha i mar-thà.

Aig àm an Dàrna Cogaidh thàinig Feachdan na Dùthcha dhan sgìre, gu h-àraidh leis na raointean-adhair a chaidh a thogail anns a’ Mhanachainn agus Tairbeart (‘the dromes’). Cuide riutha thàinig mòran bhall-seirbheise agus luchd-obrach à pàirtean eile den Rìoghhachd Aonaichte, agus bhiodh daoine na sgìre ag obair còmhla riutha, m.e. air làraich-thogail no anns na h-ionadan-bìdh (bha fear ann faisg air far a bheil an Seaboard Hall an-diugh). Dh’fhàg mòran daoine òga an sgìre leis na Feachdan cuideachd, na h-iasgairean na b’ òige nam measg. Cha robh a’ Ghàidhlig feumail no freagarrach idir anns a‘ chonaltradh an-sin – agus ‘s ann sean-fhasanta a bha i mar-thà.

Le còmhdhail na b’ fheàrr (m.e. rathaidean leasaichte san sgìre, bus-sgoile gu Acadamaidh Bhaile Dhubhthaich, agus seirbheis-trèana math air feadh na h-Alba), agus barrachd ùidh ann am foghlam agus ann an trèanadh (agus rè ùine tabhartais-chuideachaidh cuideachd), ghabh barrachd daoine òga cothrom falbh dhan oilthigh no dhan cholaiste ann an Obar-Dheathain no Dùn Èideann. ‘S e saoghal gu tur eadar-dhealaichte a bha anns na bailtean-iasgaich a-nis, gun mòran chothroman aig luchd-labhairt na Gàidhlig an cànan a bhruidhinn, agus iad gu tric gun chomas litrichean Gàidhig a sgrìobhadh gu càirdean sna Feachdan no aig a’ cholaiste; bha na sgoiltean gu h-oifigeil an aghaidh na Gàidhlig, mar a chunnaic sinn.

Ann an cruinneachadh Scottish Gaelic Dialects Survey, leughaidh sinn aiste à 1958 mu tè ann an Seannduig: “Aged 70, born Shandwick, brought up Shandwick, parents Shandwick. A very good informant, fluent in Gaelic, though with a somewhat limited vocabulary. No knowledge of written Gaelic. Used to speak the language regularly with an uncle until he died fairly recently. ” Bho na 50an agus na 60ean a-mach bha cothroman-cleachdaidh na Gàidhlig a’ lùghdachadh, fiù ‘s am measg luchd-labhairt fileanta.

Anns an darna leth den fhicheadamh linn, mar sin, cha robh Gàidhlig anns na sgoiltean tuilleadh, cha robh mòran mhinistearan ann leis a’ Ghàidhlig, agus bha an luchd-labhairt fileanta a bha air fhàgail gu math aosta, gun a bhith air mòran Gàidhlig a thoirt seachad chun na cloinne. Ach anns na bailtean-iasgaich tha daoine ann fhathast an-diùgh aig an robh na pàrantan a’ bruidhinn Gàidhlig mar chiad chànan, ri chèile agus am measg charaidean den aon aois, a-nuas chun nan trì-ficheadan co-dhiù, agus feadhainn eile chun nan seachdadan, mar Isbeil Anna bean MhicAonghais, màthair Dolaidh againn fhìn. Rinn Seòsamh Watson, na ollamh ann an Baile Àth Cliath, cruinneachadh beòil-aithris Ghàidhlig ann an Baile a’ Chnuic agus Seannduaig aig an àm sin (ri leughadh ann an Saoghal Bana-mharaiche). Tha co-dhiù cuid bheag de Ghàidhlig fhathast aig “clann” a’ ghinealaich sin (is iad fhèin nan naochadan an-diugh). A rèir cunntas-sluaigh 1971 bha Gàidhlig fhathast aig 4.8% ann am Paraiste na Manachainn, ach mar a tha fios againn bha a’ Ghàidhlig riamh na bu treasa sna bailtean-iasgaich agus mar sin tha e coltach gun robh ìre na ceud na b’ àirde ann an sin fhathast.

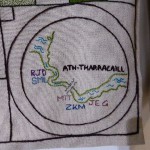

Leis a’ ghnìomhachas ùr agus na cothroman-obrach a thàinig gu Ros an Ear o chionn nan seachdadan (taigh-staile agus leaghadair alùmanuim ann an Inbhir Ghòrdain, gàrraidhean chruinn-ola ann an Neig) dh’fhàs an uimhir de cho-obraichean à ceann a deas na h-Alba, mar a thachair roimhe leis an luchd-obrach air na tuathanasan, agus lùghdaich a’ chuid de luchd na Gàidhlig anns a’ pharaiste gu 3.8% ann an 1991. Bhiodh sinn an dùil gum biodh lùghdachadh mòr eile ann an cunntas-sluaigh 2001, ach ‘s e 3.3% a bha ann fhathast, agus bha fiù ‘s meudachadh beag aig Baile an Droma agus Bhaile Dhubhthaich (Chan eil figearan mionaideach ionadail ri fhaighinn bho chunntas-sluaigh 2011 fhathast.)

Leis a’ ghnìomhachas ùr agus na cothroman-obrach a thàinig gu Ros an Ear o chionn nan seachdadan (taigh-staile agus leaghadair alùmanuim ann an Inbhir Ghòrdain, gàrraidhean chruinn-ola ann an Neig) dh’fhàs an uimhir de cho-obraichean à ceann a deas na h-Alba, mar a thachair roimhe leis an luchd-obrach air na tuathanasan, agus lùghdaich a’ chuid de luchd na Gàidhlig anns a’ pharaiste gu 3.8% ann an 1991. Bhiodh sinn an dùil gum biodh lùghdachadh mòr eile ann an cunntas-sluaigh 2001, ach ‘s e 3.3% a bha ann fhathast, agus bha fiù ‘s meudachadh beag aig Baile an Droma agus Bhaile Dhubhthaich (Chan eil figearan mionaideach ionadail ri fhaighinn bho chunntas-sluaigh 2011 fhathast.)

Carson a bha meudachadh anns na pàirtean far an robh a’ Bheurla na bu treasa – baile ‘mòr’ Bhaile Dhubhthaich agus baile tuathanais Bhaile an Droma? Ann an coimhead air na sgilean-cànain Gàidhlig san sgìre anns na cunntasan-sluaigh 1971, 1991 agus 2001, chithear an fhreagairt: foghlam. Bha Gàidhlig anns na sgoiltean a-rithist. Eadar 1971 agus 2001 mheudaich àireamh dhaoine le comas-leughaidh agus comas sgrìobhaidh na Gàidhlig ann an Rois an Ear le barrachd air 50%. Tha fios againn cuideachd mu chomas Gàidhlig a rèir aois ann an 2001. Chithear gun robh barrachd Gàidhlig aig na sgoilearan à Baile Dhubhthaich (7.5%) na aig na pàrantan (4.1%), ach bha (beagan) barrachd Gàidhlig aig na pàrantan ann am paraiste na Manachainn (leis na bailtean-iasgach).

‘S ann anns na h-ochdadan a thòisich cròileagan ann an Ros an Ear agus ann an 1987 dh’fhosgail a’ chiad Aonad Gàidhlig ann am Baile Dhubhthaich. An uairsin fhuair am baile sgoil-àraich Ghàidhlig agus foghlam tro mheadhan na Gàidhlig ann am bun-sgoil Craighill, agus foghlam Gàidhlig anns an Acadamaidh cuideachd. Nuair a dh’fhaighnich mi ann an 2012, bha a’ mhòr-chuid de na sgoilearan Gàidhlig à Baile Dhubhthaich, Baile an Droma agus Port Mo Cholmaig – chan ann às na bailtean-iasgaich fhèin, ach san fharsaingeachd ‘s e comharra brosnachail dhan Ghàidhlig anns an sgìre a th’ ann. Uaireannan ‘s e daoine à taobh a-muigh a chuireas luach an toiseach air an dualchas againn fhèin.

Ann an dòigh tha e ìoranta gu bheil an dòchas a tha againn airson Gàidhlig san àm ri teachd stèidhichte ann am Baile Dhubhthaich – a’ phàirt as “Beurlaichte” den sgìre fad linntean, agus anns na sgoiltean, far an robh Gàidhlig air a mùchadh cho fada. Chan e dualchainnt nam bailtean-iasgaich a bhios ga cluinntinn anns a’ pharaiste tuilleadh, ach Gàidhlig “mid-Minch” (measgachadh Gàidhlig nan Eileanan agus Gàidhlig na mhòr-thìr), a rèir coltais, mar a bhios ann an sgoil sam bith san latha an-diugh (rannsachadh le William Lamb 2012). Mar a thachras ann an Eurabol (rannsachadh Helen Dorian 1981), nuair a chaochlas daoine as aosta na paraiste le an cuid glè glè bheag de Ghàidhlig ionadail, cha bhi Gàidhlig Mhachair Rois ann tuilleadh ach ann an leabhraichean sgoilearach, mar Saoghal Bana-mharaiche le Seòsamh Watson.

Ann an dòigh tha e ìoranta gu bheil an dòchas a tha againn airson Gàidhlig san àm ri teachd stèidhichte ann am Baile Dhubhthaich – a’ phàirt as “Beurlaichte” den sgìre fad linntean, agus anns na sgoiltean, far an robh Gàidhlig air a mùchadh cho fada. Chan e dualchainnt nam bailtean-iasgaich a bhios ga cluinntinn anns a’ pharaiste tuilleadh, ach Gàidhlig “mid-Minch” (measgachadh Gàidhlig nan Eileanan agus Gàidhlig na mhòr-thìr), a rèir coltais, mar a bhios ann an sgoil sam bith san latha an-diugh (rannsachadh le William Lamb 2012). Mar a thachras ann an Eurabol (rannsachadh Helen Dorian 1981), nuair a chaochlas daoine as aosta na paraiste le an cuid glè glè bheag de Ghàidhlig ionadail, cha bhi Gàidhlig Mhachair Rois ann tuilleadh ach ann an leabhraichean sgoilearach, mar Saoghal Bana-mharaiche le Seòsamh Watson.

Ach mu dheireadh thall tha Gàidhlig ann. Bidh soidhneachan ùra dà-chananach ann, tha an colbh dà-chànanach seo anns an Seaboard News, agus leis an ùidh a tha ann a-rithist ann an dualchas iasgaich agus eachdraidh Mhachair Rois (m.e. sreath thachartasan Dualchas anns an Seaboard Hall), tha e coltach gum bi àite ann don Ghàidhlig san àm ri teachd. Mar a sgrìobh neach-rannsachaidh Karl Duwe ann an 2005: “Taobh Sear Rois is on the brink of language viability”. Ann an 2014 chan eil seo cinnteach fhathast, ach faodaidh sinn a bhith dòchasach.

Dealbhan bho àm a’ Chogaidh an seo: http://seaboardhistory.calicosites.com/gallery/war/

Dealbhan raon-adhair na Manachainn an seo: http://www.28dayslater.co.uk/forums/military-sites/26057-fearn-drome-accomodation-camp-easter-ross-16-01-08-a.html

*****************************************************************************

Gaelic in Seaboard History Part 4:

From World War 2 up to now: the English-speaking generations

During World War 2 the Armed Forces had a strong presence in the area, especially with the building of the airfields in Fearn and Tarbat parishes (the ‘dromes’). With them came numerous service and ancillary personnel from other parts of the UK, and locals would work alongside them, e.g. on the building sites or in canteens (there was one near where the Seaboard Hall is now), speaking English. Many young people also left the area to join the Forces, including the younger fishermen (who would still have been using at least some Gaelic with the older ones). Gaelic was no longer useful or relevant for communicating there, and it was already seen as old-fashioned.

During World War 2 the Armed Forces had a strong presence in the area, especially with the building of the airfields in Fearn and Tarbat parishes (the ‘dromes’). With them came numerous service and ancillary personnel from other parts of the UK, and locals would work alongside them, e.g. on the building sites or in canteens (there was one near where the Seaboard Hall is now), speaking English. Many young people also left the area to join the Forces, including the younger fishermen (who would still have been using at least some Gaelic with the older ones). Gaelic was no longer useful or relevant for communicating there, and it was already seen as old-fashioned.

With better transport (e.g. improved roads, school buses to Tain, and good rail connections throughout Scotland), more interest in education and training, and in due course the availability of grants for this too, more young people took advantage of the opportunity to go to college or university in Aberdeen or Edinburgh. The world of the Villages was quite changed now, with few opportunities to speak Gaelic, and often no Gaelic writing skills to correspond with relatives in the Forces or at college – the schools had long been against Gaelic, as we saw.

In the collection Scottish Gaelic Dialects Survey we can read a fieldworker’s report from 1958 about a typical elderly lady in Shandwick: “Aged 70, born Shandwick, brought up Shandwick, parents Shandwick. A very good informant, fluent in Gaelic, though with a somewhat limited vocabulary. No knowledge of written Gaelic. Used to speak the language regularly with an uncle until he died fairly recently.” From the 1950s and 1960s on, opportunities to actually use Gaelic were decreasing, even among fluent speakers.

In the second half of the 20th century in Easter Ross, then, there was no longer any Gaelic in the schools, fewer ministers spoke Gaelic, and the fluent speakers were growing old without having passed on much Gaelic to their children. But in the Villages there are still residents today whose parents spoke Gaelic as their first language, to each other and among friends of the same generation, up until the 1960s anyway, and some into the 1970s, notably such as Bell Ann MacAngus, our own Dolly’s mother. Professor Joseph Watson of Dublin University collected Gaelic oral traditions from her and others on the Seaboard at that time, which can be read in his book Saoghal Ban-mharaiche. Some of the ‘children’ of these speakers (in their 90’s themselves now) still have at least a bit of local Gaelic. According to the 1971 census 4.8% of the population of the parish of Fearn were Gaelic speakers, but given that Gaelic had always been much stronger on the Seaboard, figures there were likely to be higher.

In the second half of the 20th century in Easter Ross, then, there was no longer any Gaelic in the schools, fewer ministers spoke Gaelic, and the fluent speakers were growing old without having passed on much Gaelic to their children. But in the Villages there are still residents today whose parents spoke Gaelic as their first language, to each other and among friends of the same generation, up until the 1960s anyway, and some into the 1970s, notably such as Bell Ann MacAngus, our own Dolly’s mother. Professor Joseph Watson of Dublin University collected Gaelic oral traditions from her and others on the Seaboard at that time, which can be read in his book Saoghal Ban-mharaiche. Some of the ‘children’ of these speakers (in their 90’s themselves now) still have at least a bit of local Gaelic. According to the 1971 census 4.8% of the population of the parish of Fearn were Gaelic speakers, but given that Gaelic had always been much stronger on the Seaboard, figures there were likely to be higher.

With new industries and jobs coming to Easter Ross in the 1970s (the distillery and the smelter in Invergordon and the oil-related work at Nigg), the number of workers coming up from the south of Scotland grew again (as with the farmworkers in the 18th and 19th centuries), and the census of 1991 showed a decrease in Gaelic speakers in Fearn parish (3.8%). We would have expected a greater decrease again in 2001, but in fact it stayed fairly steady at 3.3%, with even a small increase in Tain and Hill of Fearn. (So far we don’t have a detailed analysis of local figures from the 2011 census.)

Why would there be an increase in traditionally the least Gaelic of communities in the area – the ‘big town’ of Tain and the inland farming settlement of Fearn? If we compare the census reports of Gaelic reading and writing skills between 1971 and 2001 (major increases in ability of over 50%), we see the reason – education; Gaelic was back in the schools again. Looking at the ages of Gaelic speakers in the 2001 census we see that children in Tain had more Gaelic (7.5%) than their parents (4.1%), although the parents in Fearn parish (i.e. including the Villages) still had a little more Gaelic than their children.

Gaelic playgroups started in Easter Ross in the 1980s and the first Gaelic unit in Tain opened in 1987. Over time the town got Gaelic preschool provision, Gaelic Medium Education in Craighill Primary School, and Gaelic education in the Academy too. Although when I enquired in 2012 it seemed that most of the pupils came from Tain, Fearn and Portmahomack, not from the Villages, i.e. not the traditional heartlands, it’s nevertheless an encouraging sign for Gaelic in the area. Sometimes it takes outsiders to appreciate what we take for granted.

In a way it’s ironic that the hope for Easter Ross Gaelic in the future is based in Tain – the most “anglicised” part of the area for centuries, and in the schools, which had suppressed Gaelic for so long. Neither will it be the old Seaboard dialect of Gaelic that future generations will hear, but probably ‘mid-Minch’ Gaelic, as researcher William Lamb has called it – the sort of standardised mixture of Islands and mainland Gaelic that is emerging from schools across the country. As happened in Embo (documented over decades by Helen Dorian), when the old folk with their remnant of the local dialect die, there will only be records left in books and field recordings, like those by Joseph Watson.

In a way it’s ironic that the hope for Easter Ross Gaelic in the future is based in Tain – the most “anglicised” part of the area for centuries, and in the schools, which had suppressed Gaelic for so long. Neither will it be the old Seaboard dialect of Gaelic that future generations will hear, but probably ‘mid-Minch’ Gaelic, as researcher William Lamb has called it – the sort of standardised mixture of Islands and mainland Gaelic that is emerging from schools across the country. As happened in Embo (documented over decades by Helen Dorian), when the old folk with their remnant of the local dialect die, there will only be records left in books and field recordings, like those by Joseph Watson.

But Gaelic is at last more visible on the Seaboard. There are the bilingual signs, this column in the Seaboard News, and with the renewed interest in local heritage and history, as demonstrated in the ongoing series of ‘Dualchas’ events in the Seaboard Hall, it looks as if there will be a place for Gaelic in the time to come. As researcher Karl Duwe wrote about Easter Ross in 2005: “Taobh Siar Rois is on the brink of (Gaelic) language viability.” In 2014 we can’t yet confirm that, but we have grounds for hope.

Wartime photos here: http://seaboardhistory.calicosites.com/gallery/war/

Photos of Fearn airfield here: http://www.28dayslater.co.uk/forums/military-sites/26057-fearn-drome-accomodation-camp-easter-ross-16-01-08-a.html