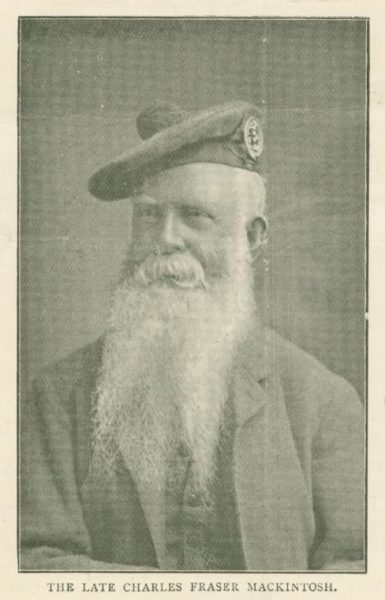

Àiteachas is iasgach an am Pearù

Reed fishing-boats

Potatoes – some of the 6000 varieties

Beagan seachdainean air ais bha mi cho fortanach is choilean mi bruadar nan làithean-sgoile agam, nuair a thachair mi air dealbhan Machu Picchu: chaidh mi a Phearù! Is e an turas as iongantaiche a rinn mi riamh, ann an iomadh dòigh – caochladh nan seallaidhean-tìre, eachdraidh nan cultaran eadar-dhealaichte tro na linntean, am biadh, na bailtean, na daoine, an fhìor-mheudachd dheth… tha mo cheann làn dealbhan, fhuaimean is fhàilidhean fhathast!

Bidh mi a’ sgrìobhadh turas eile mun eachdraidh, ach am mìos seo bha mi airson rudeigin a ràdh mu na chunnaic mi de thuathanasachd is de dh’iasgach, is iad cuspairean ceangailte ris an sgìre againne.

Thòisich sinn air an raonach ri taobh cladach a’ Chuain Sèimh tuath air Lima, is e fàsach a th’ ann gu nàdarrach. Ach b’ urrainn do na treubhan tùsanach tràtha den sgìre, gu h-àraidh na Moche is na Chimù (ro na h-Incas is na Spainntich, am fàsach uisgeachadh le sruthan as na h-Andes, siostam a bhios ga chleachadh an-diugh fhèin fhathast airson nam plantachasan-siùcair mòra, cruithneachd Innseanaich, buntàta, agus ann an àitichean cofaidh. Chleachdadh iad cuideachd am pailteas de dh’èisg a thug na làin-mhara àrda aig El Nino gus lagùnaichean daonna-dhèante a lìonadh. Chì thu seo anns an obair-shnaidhidh agus na dealbhan air a’ bhathar-criadha aca. Agus bidh muinntir a’ chladaich a’ cleachdadh an aon seòrsa bàta-iasgaich bhig dhèanta à cuilc chun an latha an-diugh. Ghabh sin ceviche, biadh-mara sònraichte le iasg ùr is mòran liomaideige, ann am baile beag iasgaich (is surfaidh), Huancacho.

Ceviche

Reed fishing boats and nets

Às dèidh an raonaich dhìrich sin suas is suas a-steach dha na h-Andes, seachad air dàm dealan-uisgeach mòr – cleachdaidh iad uisge gu math ann am Pearù – agus chuir e iongnadh oirnn dè bhios a’ fàs cho àrd. Aig 2000-4000 meatair os cionn na mara, fada nas àirde na Beinn Neibhis, tha srathan torrach le bailtean meudmhor mar Cajamarca, tuathanasan beaga, agus coilltean, air an uisgeachadh le lochan is aibhnichean, agus a-rithist le canàlan simplidh ach èifeachdach. Thadail sinn air fear drùidhteach aig Cume Mayo bho 1500-1000 ro Chrìosda. Chunnaic sinn cuideachd loin-eisg airson an tilapia bhlasda.

Hydro-electric dam

fish ponds

Anns an 20. linn chaidh craobhan eucalyptus a chur sna beanntan gus cuideachadh an aghaidh bleith-thalmhainn, gu soirbheachail, is tha iad glè fheumail a-nis airson connaidh is stuth-togalach. Tha an tuathanasachd gu math simplidh, seann-fhasanta shuas an seo – chunnaic sinn treabhadh le daimh, agus bha cearcan, gobhair is mucan a’ ruith ri taobh na rathaidean air an dùthaich. Agus bha mi toilichte buntàta fhaicinn cho àrd – tha Pearù ainmeal airson nan 6000 seòrsachan eadar-dhealaichte! Tha na margaidean ionadail dìreach mìorbhaileach.

Às dèidh sin bha sinn ann an sgìre nas àirde timcheall air Chachapoyas, Andes a‘ Choille-Sgòtha, far a chùmas adhar blàth bhon Amazon an fhàs-bheatha mèath agus leth-thropaigeach, agus na craobhan ri taobh na h-aibhne làn bromeliads. Tha flùraichean mar hibiscus air feadh an àite.

San t-seachdain mu dheireadh (à trì), bha mi sìos san taobh a deas gus tadhail air Srath Naomh nan Incas, agus a-rithist chuir an torrachd aig àirdean anabarrach iongnadh orm. Air an raonach àrd aig Moray (Phearù!), mu 3500 m, bha achaidhean farsaing ann le coirce, cruithneachd agus eòrna, sìol mar quinua, agus a-rithist buntàta – tha seòrsachan ann a dh’fhàsas aig 5000 meatair! Sìos air an raonach tha achaidhean-uisge ris ann cuideachd – pàirt chudromach den bhun-bhiadh. Ach nuair a dh’fhaighnich mi dè rinn iad leis an eòrna, cha robh mi an dùil seo a chluinntinn – an àite uisge-beatha a dhèanamh (nì iad deoch à cruithneachd Innseanach), bidh iad a’ beathachadh nan gearra-mhucan leis! Thèid a ghearradh buileach sìos fhad ‘s a tha e uaine fhathast, agus a thoirt gu lèir dhaibh. Bidh iadsan gan cumail mar chearcan anns a’ ghàrradh, agus gan ithe do dh’fhèilltean sònraichte, mar an Nollaig no co-làithean-breith.

Anns gach àite ann am Pearù tha measan ann – dearcan mar an fheadhainn againne, agus cuideachd papayas, mangos, tomàtothan-craoibh, measan-dràgain, measan-siotrachais, fìon-dhearcan, cnòthan-chòco, agus gach seòrsa tiùbair. Bidh tòrr mheasan gan ithe dhan bhracaist no gan òl mar shugh, agus tha deòch ùrachail ann dèanta le cruithneachd Innseanach purpaidh, chicha morada. Tha iad measail cuideachd air pisco, spiorad làidir dèanta à fìon-dhearcan, gu h-àraidh san cocktail pisco sour. Tha Pearù aimeil airson a thioclaid cuideachd, agus tha a ghnìomhacas fìona, ged a tha e òg fhathast, gu math gealltanach.

‘S e dùthaich bheartach chaochlaideach a th’ innte, agus anabarrach inntinneach a thaobh fàs-bheatha leis an dualchas fada de shaochrachadh-bìdh aig àirde. Is fhiach e a thadhail do chroitear no thuathanach sam bith!

Mangos

Coconuts

Farming and fishing in Peru

A few weeks ago I was lucky enough to fulfil a dream from my schooldays, when I first came across pictures of Machu Picchu – I went to Peru! It’s the most amazing trip I’ve ever done, in many ways – the variety of landscapes, the history of the different cultures through the centuries, the food, the towns, the people, and the sheer scale of it … my head is still full of the sights, sounds and smells!

I’ll write about the history another time, but this month I wanted to say something about what I saw of farming and fishing there, subjects close to our own area.

Sugar cane

Rice-paddies

We started off in the coastal plain north of Lima, which is naturally a desert. But the early peoples of the area, especially the Moche and the Chimù (pre-Inca and pre-Spanish), learned how to irrigate the desert with water from the Andes – a system still in use today, mainly to allow vast sugar plantations, maize, potatoes, and in some areas coffee beans. They also exploited the fairly regular El Nino high tides to store the glut of fish they brought in man-made lagoons. This is all recorded in their carvings, ceramics etc. The type of little reed fishing boat still in use today is the same as on ancient carvings. We enjoyed the coastal speciality ceviche, made with fresh fish and lots of lime, in a small fishing (and surfing) town, Huancacho.

After the plains we went up and up into the Andes, past a huge hydro-electric dam – water is well used in Peru – and were amazed at how much still grows so high up. At heights well above Ben Nevis, 2000 to 4000 metres above sea level, there are fertile valleys with sizeable towns like Cajamarca, croft-like farms, and woods, all watered by lakes and rivers, and again with simple but effective irrigation canals. One impressive one we visited at Cume Mayo goes back to 1500-1000 BC. We also saw what looked like trout ponds, used for their tasty tilapia.

Cume Mayo prehistoric aqueduct

Inca agricultural terraces, Pisaq

In the 20th C. eucalyptus trees were introduced to help stop soil erosion, and they have flourished, providing fuel and building materials. Farming is fairly unsophisticated up there – we saw ox-ploughs in use, and hens, goats and pigs run around by the wayside. And I was happy to see some of the taties that Peru is famous for – it has over 6000 varieties! The local markets are just wonderful.

Later we were in a higher region around Chachapoyas, the Cloud Forest Andes, where warm, humid air from the Amazon keeps vegetation lush and semi-tropical, and the trees along the rivers are full of bromeliads. Flowers like hibiscus are everywhere.

In my last week (of three), I was down in the south of Peru, to visit the Sacred Valley of the Incas, and again the fertility at high altitude was astonishing. On the high plains of (Peruvian) Moray (c. 3500 m) there are wide fields of grain – oats, wheat and barley, seeds like quinua, and again potatoes – some varieties grow as high as 5000 metres! Down on the flatlands there are rice paddies too, an important part of their diet. But I got a surprise when I asked what the barley was used for – not for whisky, but to feed the guinea-pigs! It’s cut right down when still green and the whole thing fed to the many domesticated piggies. People keep them in their back gardens like hens, and eat them for special occasions, like Christmas and birthdays.

Scottish broom on the Moray High Plains

Grain at 3500m

Everywhere in Peru there’s also fruit – berries like ours and also papayas, mangos, tree-tomatoes, dragon-fruit, citrus, grapes, coconuts and every kind of tuber. A lot of fruit is eaten at breakfast or drunk as juice, and a popular soft drink is a juice made from purple maize, chicha morada. The strong grape spirit pisco is also popular, especially as the pisco sour cocktail. Peru is also famous for its chocolate, and its still young wine industry is also promising.

It’s a rich and varied country, and exceptionally interesting as regards vegetation and the long tradition of food production at altitude. Well worth a visit for any crofters and farmers!

Potato varieties

Various corns

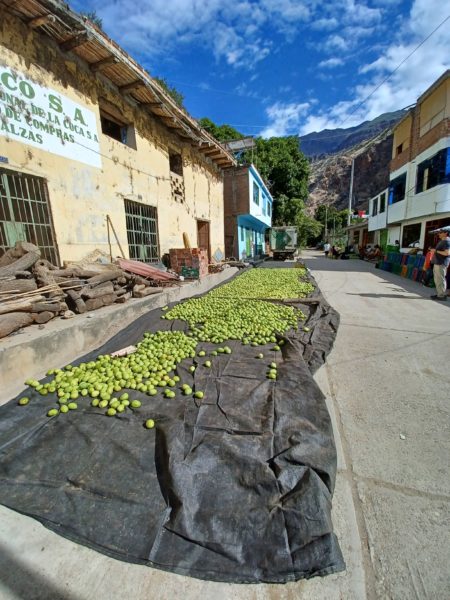

Coffee-drying plant

Rural transport

sugar-cane

Ice-cream van

coffee beans