Northumberland: Bamburgh

Eadar an Nollaig agus a’ Bhliadhn’ Ùr bha cothrom agam beagan làithean a chur seachad còmhla ri caraid agus an dà chù aice ann an Northumberland. Tha, ‘s dòcha, 20 bliadhna bhon a bha mi san sgìre sin, ach a-mhàin san dol seachad, agus leis gun do chòrd i rium glan an turas mu dheireadh, bha mi a’ dèanamh fiughair ri a faicinn a-rithist. Agus chan e briseadh-dùil a bh’ ann idir – àite cho àlainn is eachdraidheil ‘s a bha e riamh. Chleachd sinn an ùine ghoirid gu math, le bhith a’ coiseachd air diofar thràighean leis na coin, agus a’ tadhal air seann chaistealean is eaglaisean (is dìreach pailteas dhiubhsan an sin).

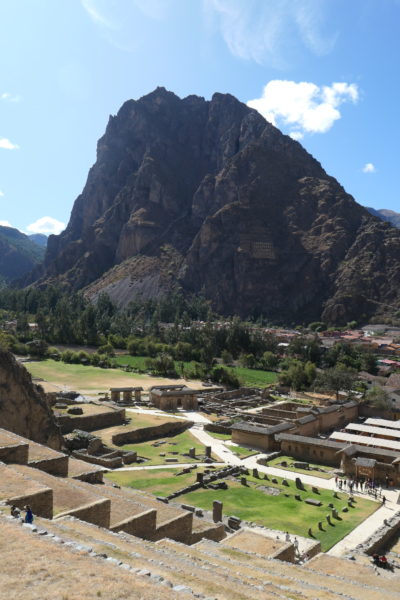

Ach an-diugh bha mi airson innse dhuibh mun chaisteal as ainmeile an sin, Bamburgh. Chì thu bho fhada e às gach àird, na shuidhe gu pròiseil air a chreig bhasailt chais sna dùin-ghainmich, dìreach ri taobh na mara am meadhan achaidhean rèidh. Sealladh druidhteach!

Bha àitichean-tuinidh air a’ chreig agus timcheall oirre fad nam miltean de bhliadhnaichean, ach ’s ann leis na rìghrean Anglach is Sagsannach a thàinig na linntean a bu chudromaiche a’ chaisteil, is iad an sàs ann an sgaoileadh Crìostaidheachd (chaidh Naomh Aodhan a chur bho Eilean Ì san 7mh linn) agus anns an dìon an aghaidh nan Lochlannach – agus nan Cruithneach. Dh’fhàs an daighneach na bhu mhotha ‘s na bu treasa thar nan linntean, fo rìoghrachasan eile, ach mu dheireadh thall cha robh fiù ‘s na ballaichean tomadach cloiche sin làidir gu leòr agus ri àm Cogaidhean nan Ròsan bha Bamburgh na chiad chaisteal san tìr a chaidh a mhilleadh le cumhachd chanan.

As dèidh sin cha deach Caisteal Bhamburgh fìor am feabhas buileach mar dhaighneach. San 18mh linn bha e na àite-fuirich Easbaig Dhurham, Lord Nathaniel Crewe, a thòisich càradh a’ chaisteil, obair a chùm Urras Lord Crewe a’ dol as a dhèidh tron 19mh linn. Bha an t-Urras cuideachd an sàs ann an ath-thogail a’ bhaile agus ann an stèidheachadh seòrsa “stàit shochairean” ionadail le ospadal, sgoil, bàta-teasairginn is eile. Ach air sgàth dhuilgheadasan ionmhasail a thàinig orra, cheannaich Lord Armstrong of Cragside an caisteal ‘s an oighreachd ann an 1894.

Agus ‘s ann fodhasan a dh’ùr-bheòthaich an caisteal, le obraichean-togail mòra agus leis an ath-chruthachadh gu bhith mar dhaighneach Mheadhan-Aoiseach a-rithist. Dh’fhuirich e fhèin ann gu tric, agus lìon e le àirneis sònraichte is ealain e. Sin an caisteal a chì thu an-diugh, agus is fìor fhiach a dhol ann – tha an togalach agus an suidheachadh (agus an sealladh) drùidhteach gu leòr iad fhèin, ach a bharrachd air sin, tha na seòmraichean diofraichte, bhon talla mhòr chun a’ chidsin, uabhasach intinneach is làn stuth tarraingeach, le mìneachaidhean soilleir ciallach annta.

Ach faodaidh mi tadhal timcheall air àm na Nollaig a mholadh gu h-àraidh. Chan ann dìreach oir cha bhi e cho trang, ach ‘s ann gum bi iad a’ sgeadachadh nan seòmraichean a-rèir cuspair Nollaige (an turas seo The Twelve Days of Christmas), gu proifeasanta ‘s gu h-àlainn, cho cruthachail is mionaideach ‘s gur gann gun creidseadh tu e. Chòrd rium gu h-àraidh na breusan sgeadaichte gu h-ealanta. ‘S e Charlotte Lloyd-Webber, dealbhaiche-tèatair, a chruthaicheas e leis an sgioba aice, mar a nì i cuideachd aig Caisteal Howard, agus is fhiach fhaicinn – chan eil mi fhìn uabhasach measail air sgeadachadh mar as àbhaist, ach ‘s e rud gu tur a-mach às an àbhaist a bha seo, aig ìre àrd ealanta; chan e kitsch a th’ ann idir. Bidh iad ga dhèanamh a-rithist san Dùbhlachd am bliadhna, a rèir coltais.

Agus mura h-eil sin gu leòr, tha am baile fhèin snog, le cafaidhean is taigh-seinnse, agus eaglais eachdraidheil, agus tha an tràigh-ghainmhich ri taobh a’ chaisteal air leth brèagha, fada, farsaing, agus dìreach taghta do theaghlaich – agus do choin. Rùm gu leòr ann dhan a h-uile duine!

https://www.bamburghcastle.com/

Northumberland: Bamburgh

Between Christmas and New Year I had the chance of a few days away with a friend and her two dogs in Northumberland. It’s maybe 20 years since I was in that area, except for passing through, and I’d enjoyed it so much the last time that I was really looking forward to it. And I wasn’t disappointed – it’s as lovely and historic as ever. We fairly packed in the beach walks, castles and old churches (and there are plenty of all these) in the short time.

But in this article I want to concentrate on the most famous castle there – Bamburgh. You can see it from far away from every direction, perched proudly on its steep basalt crag in the dunes, right by the sea, amid flat farmland. An impressive sight!

There have been settlements on the crag and around it for thousands of years, but it was under the kings of the Angles and the Saxons that it had its most important centuries, being involved in the spread of Christianity (St Aiden was sent there from Iona in the 7th C) and the defence against the Vikings – and the Picts. The fortress grew larger and stronger over the centuries under other dynasties, but even these massive stone walls were not enough to stop it becoming the first castle in the country to fall to canon, during the Wars of the Roses.

After that Bamburgh Castle never really fully recovered as a military stronghold. In the 18th C it was the residence of the Bishop of Durham, Lord Nathaniel Crewe, who began to repair it, work which was continued after him by the Lord Crewe Trust through the 19th C. The Trust was also active in rebuilding the village, and it established a kind of local “welfare state” with hospital, school, lifeboat etc. But due to financial difficulties that befell them, Lord Armstrong of Cragside bought the castle and estate in 1894.

It was under him that the castle saw a revival, with major building works and restoration back into a mediaeval fortress. He often stayed in the castle himself, and filled it with sumptuous furniture and art. That’s the castle we see today, and it’s absolutely worth going to see it – the building and its location (and view) themselves are impressive enough, but also the different rooms inside, from the great hall to the kitchen, are extremely interesting, full of fascinating objects, with clear, discreet explanations.

But I can especially recommend a visit around Christmas. Not just because it’s less busy, but also because they decorate the rooms with a Christmas theme (this year it was The Twelve Days of Christmas), professionally and beautifully; it’s so creative and detailed that it’s hard to believe. I particularly admired the beautiful, elaborate fireplace decoration. It’s the theatre-designer Charlotte Lloyd-Webber and her team who create it, as they also do at Castle Howard, and it’s really worth seeing – ordinarily I’m not very keen on decoration, but this was something altogether out of the ordinary, at a high level of artistry, no hint of kitsch. They’re doing it again this December, apparently.

And if all that wasn’t enough, the village itself is lovely, with cafes and a pub, and a historic church, and there’s an exceptionally beautiful long, wide sandy beach right beside the castle, just perfect for families – and for dogs. Plenty of room there for everyone!

https://www.bamburghcastle.com/