Guest article by Anne Barclay of Golspie. Mòran taing, Anne!

A book and a film: East Sutherland Gaelic Heritage Night featured “Mar a Chunnaic Mise: Nancy Dorian is a’ Ghaidhlig “ – a documentary following linguist Nancy Dorian, who studied the last of the East Sutherland Gaelic speakers. What an interesting evening it turned out to be!

Aileen Ogilvie introduced Professor Neil Simco from the University of the Highlands and Islands, Dornoch Campus, who explained his own interest in the Gaelic language. He is an Englishman who studied Gaelic at Sabhal Mor Ostaig and is fluent in the language albeit with an English accent for which he apologised. He attained his fluency by using the Gaelic language at every opportunity. He told us how there is research going on at present into the crisis within the Gaelic language and the state of Gaelic in the Western Isles. At UHI, they try to make the student experience bilingual, corporate communication is also bilingual, and staff have the opportunity to learn Gaelic. Prof Simco switched easily from Gaelic to English right throughout.

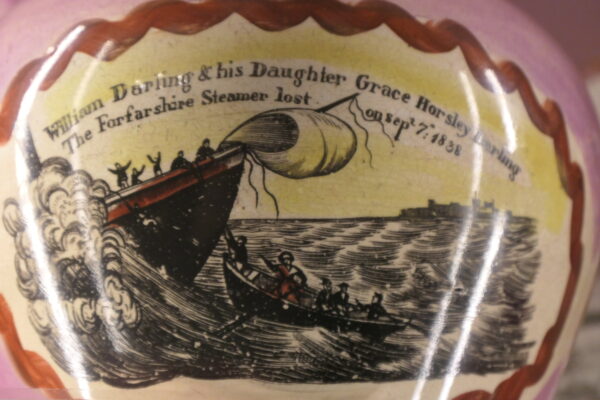

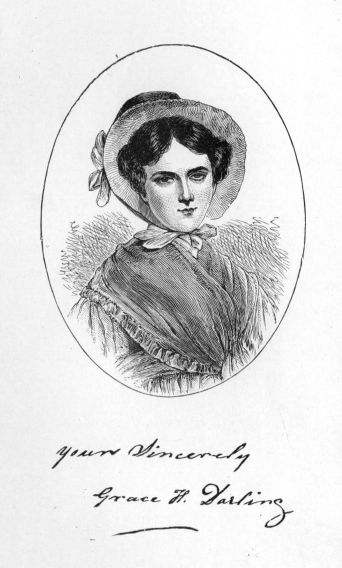

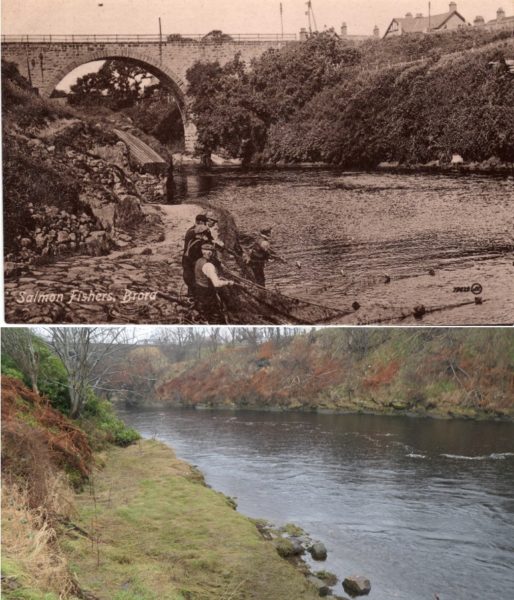

Aileen Ogilvie, herself a Gaelic speaker, introduced the film which had been made some time ago, probably in the 1980’s, and featured Nancy Dorian, a Professor of Linguistics from the eastern seaboard of America who studied the last of the East Sutherland Gaelic speakers. East Sutherland Gaelic was spoken mainly in the fishing communities pf Brora, Golspie and Embo. Of the three villages only Embo was a totally fishing village. Brora’s fishing community was confined to Lower Brora beside the mouth of the river, while in Golspie it was the West End of the village. Gaelic was not spoken in the rest of Brora nor in the East End of Golspie. In the film we saw Nancy Dorian at work in her study in America, checking her pronunciation of Gaelic words over the telephone with the friends she had made in East Sutherland. She wanted to have the authentic East Sutherland accent and spelling of words and this she certainly achieved.

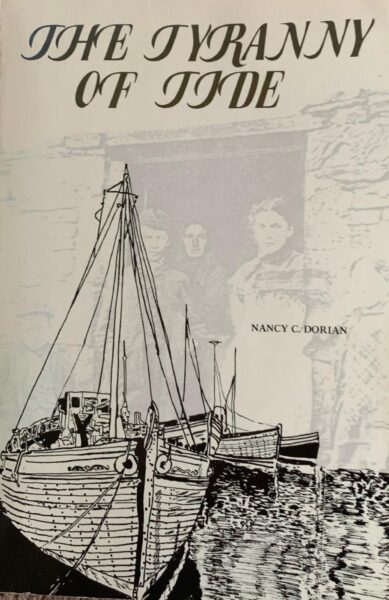

Her friendship with the last Gaelic speakers from East Sutherland lasted throughout their lives and the film is testament to the work she did over many years. Nancy Dorian also wrote a book called “The Tyranny of the Tide” where she documented the oral history of the fishing in East Sutherland, the stories of the people, the local fishing, the role of women in the family, religion, their beliefs and practices. This she wrote down largely in the words of the people she spoke to and lived among from time to time over many years.

There are numerous examples in the book where the stories are told by the people. One woman talking about her lack of education is quoted here. “I used to get rows Nancy, from the teachers….They thought I should be in school….my mother was very keen to send me when she could….sometimes she would keep my eldest brother off school but it was mostly me. Because I was handier in the house than a boy anyway.” When describing the decision of where to fish on any day, and she is talking about line fishing, it was supposed to be by common agreement, but the young men always deferred to the older men. “ If the older man says, ‘We’ll go here’ they never said yes or no, whether they thought otherwise or not…..they never mentioned it. They always gave “an t-urram do’n aois “(Honour to age).

Nancy Dorian had the ability to insert Gaelic words, still in use when she made her oral history recordings, to great effect throughout the book. “The Tyranny of the Tide” is a book I have read several times in the years I have spent in Golspie and I am always struck by the similarities there are to the Seaboard fishing villages. As in the Seaboard Gaelic has died out but words and phrases remain to remind us of our heritage.

This is a snatch of an old song that Nancy Dorian recorded from the Sutherland family she spent much time with in the 1970’s.

“S iomadh caileag bhoidheach

Eadar Dornach ’s a’ bhail’ seo

‘A do chuuir i treimh brog air

Bu bhoidhich’ na mo chaileagas. “

There’s many a bonny lass Between Dornoch and this village:

There didn’t step a foot (A girl) bonnier than my lass.

(Chaochail Nancy Dorian 24.04.24, aois 87, dìreach às dèidh foillseachadh an artaigil seo. Fìor bhana-ghaisgeach na Gàidhlig. Clach air a càrn. / Nancy Dorian died on 24.04.24, aged 87, just after the publication of this article. A true hero of Gaelic. May her memory live on.)

Golspie

Golspie

Embo

Embo