‘S ann anns a’ Ghearran a tha mi a’ sgrìobhadh seo, àm nan gealagan-làir. Anns na mìosan dubha den gheamhradh bidh sinn a’ fèitheamh air a’ chiad sealladh dhiubh, is iadsan comharra an earraich ri teachd, geal mar an sneachd agus deàrrsach mar sholas na maidne. Anns a’ Ghàidhlig tha an t-ainm a’ ciallachadh “rud beag geal an talmhainn”, ach tha ainm eile ann cuideachd, blàth-sneachda – “flùr den t-sneachd”. Uaireannan bidh iad a’ nochdadh tron t-sneachd fhèin, uaireannan am measg dhuilleagan donn seargte, ach an-còmhnaidh nan samhla di-beathte dòchais.

Mar sin is beag an t-iongnadh gun nochd a‘ ghealag-làir anns a‘ bheul-aithris mar lus sònraichte. Chì sinn aon deagh eisimpleir san uirsgeul Biara, Brìde is Aonghas. B’ e Banrigh a’ Gheamhraidh a bha ann am Biora Dhorcha, boireannach mòr, grannda, cruaidh, agus chùm i Brìde, bana-phrionnsa òg, àlainn, mar phrìosanach, ag obair na tràill. Aon latha thill Brìde air ais bhon allt reòthte far am b’ fheudar dhi clòimh bho chaora dhonn a nighe geal, saothair gun fheum, le bad ghealagan-làir na làimh, agus abair fearg a bha air Biara, is fios aice gum biodh an rìoghachadh aice a tighinn gu crìoch. Dh’fheuch i a h-uile rud gus an geamhradh a chumail a’ dol, le stoirmean is gaillinn-sneachda air feadh na h-Alba, ach aig a cheann thall chaidh aig a’ Phrionnsa Aonghas nan Òg às an Eilean Uaine (seòrsa Tìr nan Òg) air Brìde a shàbhaladh, agus chaill Biara a cumhachd. Thàinig an t-earrach agus rìoghaich Aonghas is Brìde mar Rìgh is Banrigh an t-Samhraidh – gus an tilleadh cumhachd Biara sa gheamhradh a-rithist.

Tha gealag-làir shònraichte a’ nochdadh ann an sgeulachd eile. Anns an fhiolm ghoirid tarraingeach Foighidinn – the Crimson Snowdrop le Simon David Miller (2005), tha duine òg uasal air an leannan aige a phuinnseanachadh le tuiteamas, agus feumaidh e an aon chungaidh-leigheis san t-saoghal a shireadh – gealag-làir chrò-dhearg, flùr dearg a‘ chridhe, a dh’fhàsadh air mullach nam beann as àirde ach a chaidh bàs o chionn linntean. Ach cumaidh e a‘ dol, fad seachd bliadhna, gus an ruig e an Cuiltheann san Eilean Sgitheanach…. ma bhios sibh ag iarraidh faighinn a-mach dè thachair an uair sin, seo am fiolm (14 mionaidean): https://vimeo.com/7855573. (14 mion.)

Às dèidh dha a bhith soirbheachail le Foighidinn, rinn Miller fiolm fada mar leasachadh den sgeulachd, Seachd – the Inaccessible Pinnacle ann an 2007 – fiolm uabhasach math cuideachd.

Tha gealagan-làir gu math cumanta ann am Breatainn, ged a tha iad nas sgaoilte air feadh a‘ Ghàidhealtachd ’s nan Eileanan, ach chan e lus dùthchail a tha innte. Tha e coltach gun tàinig iad às a‘ mhòr-thìr Eòrpach mar fhlùraichean sgeadachail san t-siathamh linn deug ach cha deach an clàradh mar lusan fiadhaich ach aig deireadh an ochdaimh linn deug. Tha seòrsaichean gu math eadar-dhealaichte ann san eadar-àm, bhon fheadhainn simplidh as fheàrr leamsa, gu cuid eile le coltas dreasaichean dannsairean-ballet. Tha daoine ann air a bheil Galanthophiles a tha gu sònraichte measail agus eòlach air gealagan-làir is iad a’ feuchainn an uiread ‘s a ghabhas de sheòrsaichean a lorg ‘s a chlàradh.

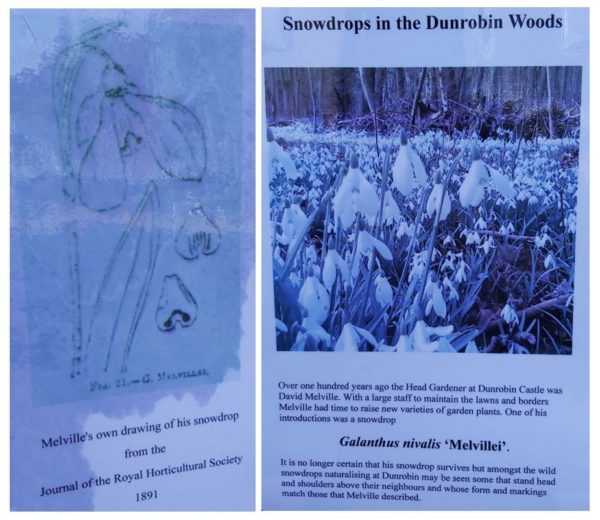

Bha mi dìreach aig Caisteal Dùn Robain gus na gealagan-làir ainmeil aca fhaicinn, agus leugh mi air sanas gun do thog an t-àrd-gàirnealair an sin, David Melville, seòrsa ùr de ghalag-làir ann an 1879, Galanthus Melvillei, agus bidh na Galanthophiles a’ feuchainn ri eisimpleirean dhi a lorg sna coilltean, agus a’ tadhail air an uaigh aig Melville sa chladh ann an Goillspidh, far a bheil diofair seòrsaichean de ghealag-làir a’ fàs.

Tha na gealagan-làir measail air coilltean agus pàircean, agus gu h-àraidh air cladhan – bidh mòran rim faicinn ann an cladhan na sgìre againne. Agus an robh sibh riamh aig Poyntzfield san Eilean Dubh sa Ghearran? ‘S e sin an làrach as fheàrr leam fhìn air an son. Tha an dà thaobh den cheum suas dhan ghàrradh-lusan loma-làn de ghealagan-làir is winter aconites buidhe. Thèid mi ann gach bliadhna a dh’aona-ghnothach.

Agus chan ann bòidheach a-mhàin a tha gealagan-làir – nì iad feum cuideachd, cuide ri conaisg, dha na seilleanan tràtha, gus an stòr poilein is meala den t-seann bhliadhna a mheudachadh. Lusan àlainn, feumail is làn dòchais – cò dh’iarradh a bharrachd!

+++++++++++++++++++++++++

Logie Wester

Nonikiln

I’m writing this in February, snowdrop season. In the dark months of winter we wait for the first sight of them, a sign of the spring to come, white as the snow and shining like the morning light. In Gaelic their usual name means “wee white thing of the ground” but they have another name too, blàth-sneachda – “blossom of the snow”. Sometimes they emerge from the snow itself, sometimes against withered brown leaves, but always a welcome sign of hope.

It’s therefore small wonder that the snowdrop appears in oral tradition and legends as a special plant. One good example is in the old tale of Biara, Angus and Bride. Biara the Dark was the Queen of Winter, a big, ugly, cruel woman, and she kept Bride, a beautiful young princess, a prisoner, working her like a slave. One day Bride returned from the frozen stream where she had to wash a brown sheep’s fleece white – a senseless task – with a bunch of snowdrops in her hand. What a rage Biara was in, knowing that her reign was coming to an end. She tried everything to keep the winter going, with storms and blizzards across Scotland, but in the end Prince Angus the Ever-young, from the Green Isle (a kind of Land of Youth), managed to rescue Bride, and Biara lost her power. The spring came and Angus and Bride ruled as King and Queen of the Summer – until Biara’s power gradually returned again in winter.

A very special snowdrop features in another story. In the gripping short film Foighidinn – the Crimson Snowdrop by Simon Miller (2005), a young nobleman has accidentally poisoned his sweetheart, and has to search for the only cure in the world – the crimson snowdrop, red flower of the heart, which grew on the highest mountain peaks but which had died out centuries ago. But he keeps going, seven years long, until he reaches the Cuillins on the Isle of Skye…. And if you want to find out what happens, you can watch the film here: https://vimeo.com/7855573. (14 mins.)

After the success of the short film, Miller made a full-length one as a development of the story in 2007 – Seachd – the Inaccessible Pinnacle. Also a wonderful film

Snowdrops are fairly common in Britain, though more scattered in the Highlands and Islands, but they’re not actually a native plant. It’s likely that they came from the European mainland as an ornamental plant in the 16th century but they were not recorded in the wild until the end of the 18th century. There are many different varieties in the meantime, from the simple ones I prefer to the ones that look like ballet-dancers’ tutus. There are people called Galanthophiles who are particularly fond of and knowledgeable about snowdrops, and who try to find and record as many varieties as possible.

I’ve just come back from a visit to Dunrobin Castle to see their famous snowdrops, and I read on a notice that a head-gardener there, David Melville, raised a new variety in 1879, Galanthus Melvillei, and the Galanthophiles go looking for it in the castle woods, and visit Melville’s grave in Golspie, which is surrounded by many varieties of snowdrop.

Snowdrops are fond of woods and parks, but especially of graveyards – you can see masses in our own local graveyards. And have you ever been to Poyntzfield on the Black Isle in February? That’s my favourite site for them. Both sides of the path up to the herb-garden are lined with carpets of snowdrops and yellow winter aconites. I go there every year specially.

But they’re not just a pretty face – they’re of use, alongside the whins, to the early bees too, supplementing their diminishing store of pollen and honey from the old year. These snowdrops are beautiful, useful, and full of hope – what more could anyone ask for!

Poyntzfield

Arisaig

Beauly

Poyntzfield

Beauly

Oldmeldrum

Oldmeldrum

Logie Wester

Logie Wester

Contin

Taing do / Thanks to Anne MacInnes (Logie Wester, Contin images) agus Allan Bremner (Oldmeldrum).