Smeuran

Leis an t-sìde bhrèagha a th’ againn a-nis (tha mi a’ sgrìobhagh seo gu deireadh na Sultaine), bidh mi a’ coiseachd a-muigh air an dùthaich cho tric ‘s a ghabhas. Agus gach uair, chan urrainn dhomh gun a bhith a’ buain nan smeuran agus ag ithe mo làn-shàth dhiubh. Tha iad cho pailt am bliadhna, agus cho blasda! Leugh mi gu bheil atharrachadh na h-aimsir a tha air a bhith againn o chionn beagan bhliadhnaichean – samhraidhean fliuch agus foghair ghrianach thioram – sònraichte math do smeuran (agus chan ann math idir do shuibheagan). Fàsaidh iad mòr sòghmhor leis an taiseachd, agus milis fo ghrian an fhoghair, agus cumaidh iad a’ dol fad mòran seachdainean.

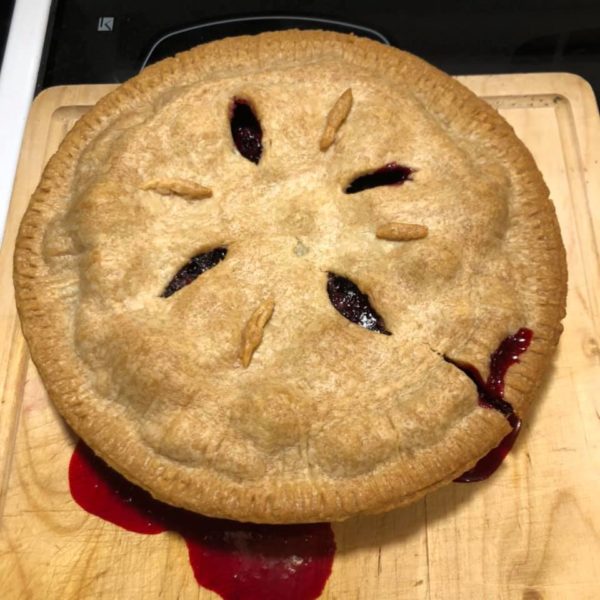

‘S e dearcan iol-chomasach a th’ anns na smeuran. ‘S urrainn dhut an ithe amh bhon phreas no ann am mìlseanan fuara, no silidh a dhèanamh, no crumbles is pàidhean (blasda cuideachd còmhla ri ùbhlan), no fìon no liciùr-sine … liosta gun chrìoch. Ach bha iad riamh aithnichte mar chungaidh-leighis cuideachd, gu h-àraidh mar fhìon-geur a tha math airson an tùchaidh, a’ chasaid agus thrioblaidean-gaillich, ach cuideachd airson na buainniche, ann an daoine agus crodh.

Ach bha taobh aig na smeuran nach robh idir cho fallain, a-rèir beòil-aithris: cha bu chòir dhut am buain ro fhadalach sa bhliadhna, air sgàth’s gur e measan an diabhail a bhiodh annta às dèidh na Samhain, no fiù ‘s às dèidh Fèill Mhìcheil. B’ urrainn dhut cuideachd duine no beathach a chur fo gheasaibh olc aig an t-Samhain le pìos dris-mheòir.

Tha na meanganan deilgneach den dris gun teagamh cunnartach gu leòr iad fhèin, gun draoidheachd sam bith eile. Dionaidh nàdar a mheasan gu math, agus bheir na drisean fasgadh do h-eòin is beathaichean beaga, fhads ’s a bhios na blàthan, na dearcan agus na duilleagan a’ còrdadh ri seilleanan agus dealain-dè. Agus na dearcan rinne cuideachd! Is fhiach daonnan e dèiligeadh ris an droigheann gus an toradh milis a bhuannachadh.

Seo seann tòimhseachan:

Is àirde e na ‘n t-each

Is lugha e na ‘n luch

Is deirge e na ‘n fhuil

Is duibhe e na ‘m fitheach.

Dè a th’ ann? Smeuran air dris!

++++++++++++++++++

Brambles

With the weather being so beautiful just now (I’m writing this towards the end of September), I go for walks out in the country as often as possible. And every time, I can’t resist picking brambles and eating my fill. They’re so plentiful this year, and so delicious! I read that the change in weather patterns the last few years – wet summers and dry, sunny autumns – are particularly good for brambles (and not good at all for rasps). They grow big and luscious with the humidity, and sweet under the autumn sun, and they keep producing for many weeks.

They’re really versatile berries. You can eat them straight from the bush, or with cold desserts, or make jam or jelly, or crumbles and tarts (tasty in with apples too), or wine or gin liqueur … it’s an endless list. But they have also always been known as a medicine, especially as a vinegar, which is good for sore throats, coughs and gum troubles, but also for diarrhoea in humans and cattle.

But there was a much less healthy side to brambles too, according to folk tradition: you shouldn’t pick them too late in the year, as they were supposedly the devil’s fruit after Halloween, or even after Michaelmas. You could also put people or animals under an evil spell with a piece of bramble branch at Halloween.

The thorny branches of the briar are certainly dangerous enough on their own, without any other magic. Nature protects her fruits well, and the briars give shelter to small birds and animals, while bees and butterflies love the blossoms, berries and leaves. And we humans love the berries too! It’s always worth coping with the thorns to win the sweet harvest.

Here’s an old riddle:

It’s taller than a horse

It’s smaller than a mouse

It’s redder than blood

It’s blacker than a raven.

What is it? A bramble on its briar!