Waipu – sgeulachd iongantach (2)

Ann am Pàirt 1 ar sgeulachd, dh’fhàg sinn an t-Urr. Tormod MacLeòid a’ meòrachadh mu eilthireachd a-rithist, a-mach à Ceap Breatainn, is a’ bheatha an sin air fàs ro dhoirbh dhan tuineachadh aige leis a’ ghort air fàire is cùisean a’ dol am miosad san fharsaingeachd. Ach càit’ an rachadh iad?

Dìreach aig an àm sin, 1848, thàinig litir à Astràilia, far an robh Dòmhnall, am mac a bu shine aige, air tuineachadh, a’ moladh beatha, fearann is aimsir thall an sin, agus a’ brosnachadh an teaghlaich a thighinn ann cuideachd. Bha sin mar chomharra do Thormod is dhan treud dìleas aige, agus cha b’ fhada gus an robh iad a’ togail long a bhiodh freagarrach dhan t-siubhal fhada – a’ Margaret, ainm nighean Thormoid, dèanta à fiodh à fearann Thormoid fhèin. Lean iad orra le togail longan eile cuideachd. Anns an Dàmhair 1851 dh’fhàg Tormod is a’ chiad 135 tuinichean Baile Anna, agus ràinig iad Adelaide anns a’ Ghiblean 1852. Lean an Highland Lass orra sìa mìosan às dèidh sin. ‘S e neach-ghnìomhachais math a bh’ ann an Tormod – reic e am fearann aige airson prìs maith gus an t-siubhal a phàigheadh is an uair sin fhuair e prìs mhath eile airson a’ Margaret ann an Sydney, gus fearann is teachd an tìr thall an sin a mhaoineachadh dhan teaghlach ‘s dhan luchd-leantainn an toiseach.

Ach bha briseadh-dùil cruaidh a’ feitheamh orra – bha Dòmhnall air imrich a Melbourne, agus cha robh fearann gu leòr dha na h-eilthirich à Ceap Breatainn gus tuineachadh a stèidheachadh ann an sgìre Adelaide. Lean iad Dòmhnall is chaidh iad a Melbourne cuideachd. Ach san eadar-àm bha Astràilia air a glacadh le fiabhras an òir, agus cha robh fearann math ri fhaighinn ach airson phrìsean ana-mhòr. B’ fheudar dhaibh fuireach ann an teantaichean còmhla ris na mìltean eile a bha air tòir an òir. Chaidh cuid de na fir a lorg obair aig na “diggings”, oir bha airgead a dhìth orra. Chunnaic Tormod gun robh a threud a’ fàs sgapte am measg mì-mhoraltachd, misg is sainnt, fada nas miosa na bha ann am Pictou às dèidh a’ chiad eilthireachd. Agus an uair sin thàinig rud fiù ‘s na bu mhiosa – am fiabhras breac. Chaochail trì de na mic aige fhèin an ceann sìa mìosan. Co-dhùin e agus a’ mhòr-chuid den treud Astràilia fhàgail.

Chuala iad gun robh fearann ri fhaighinn ann an Eilean a Tuath, Sealainn Nuadh – agus leis nach robh òr an sin, bhiodh cùisean na bu shàmhaiche, is na bu shaoire. Sgrìobh Tormod litir dhan Riaghladair agus fhuair iad cead tuineachadh an sin, agus fiù ‘s leis a h-uile duine ann an aon sgìre, gus am biodh an treud còmhla agus Gàidhlig ga bruidhinn. Reic iad an Highland Lass agus cheannaich iad an Gazelle. Ràinig iad Auckland an an 1853 agus às dèidh iomadh dàil is duilgheadas fhuair iad cead tuineachadh ann an sgìre Waipu, fearann air a cheannachd bho na Maoiri leis an Riaghaltas, an ceann a tuath Eilein a Tuath. Dh’fhuirich cuid à Alba Nuadh ann an Adelaide is Melbourne, cuid eile ann an Auckland, far an robh iomadh Gàidheal eile, ach bha deagh bhuidheann air fhàgail airson an tuineachaidh ùir ann an Waipu bho 1854 a-mach.

Leig iad fios gu Baile Anna dè cho freagarrach ‘s a bha an t-àite, agus thàinig ceithir longan eile à Ceap Breatainn a Waipu, is mu 900 daoine a’ fuireach an sin an ceann ùine ghoirid. Seo na longan mu dheireadh ar sgeulachd: Gertrude (1856), Spray (1857), Breadalbane (1858), agus Ellen Lewis (1860)

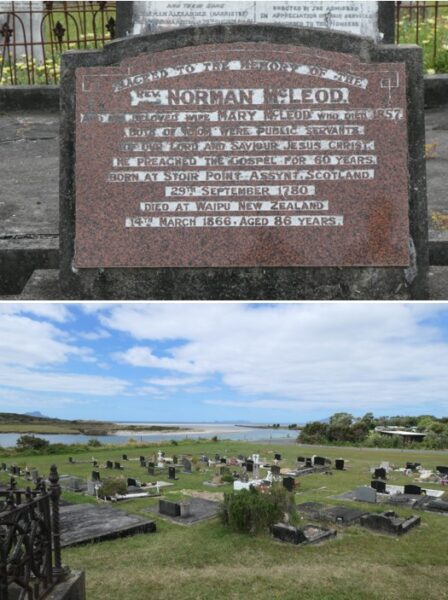

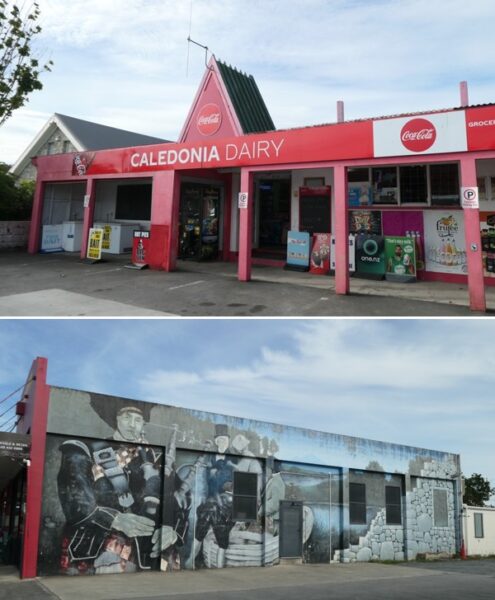

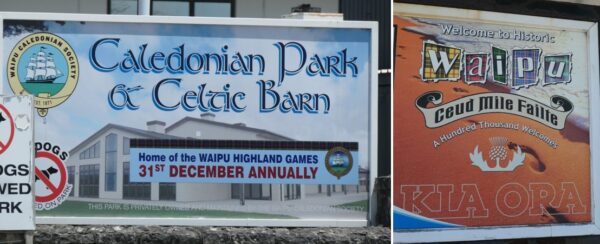

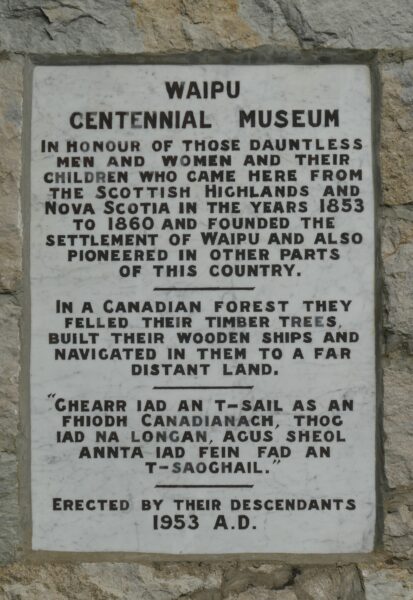

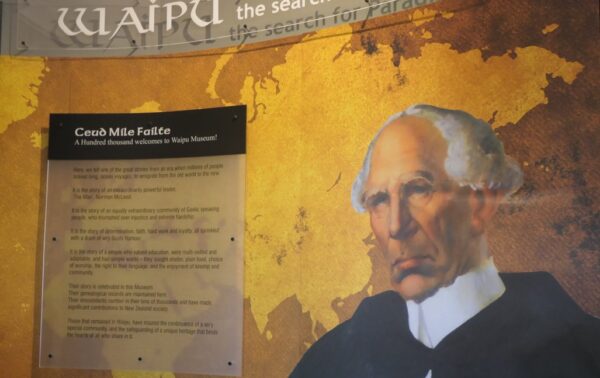

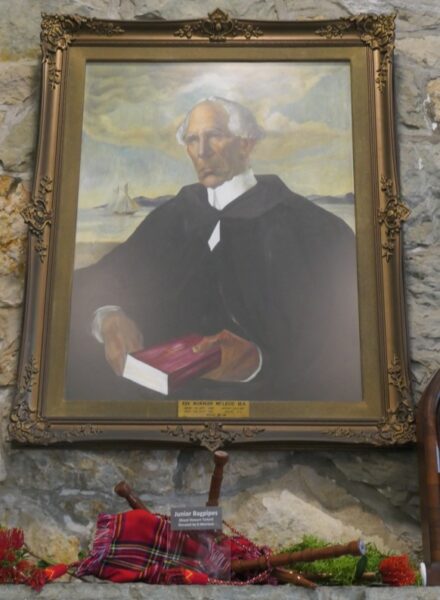

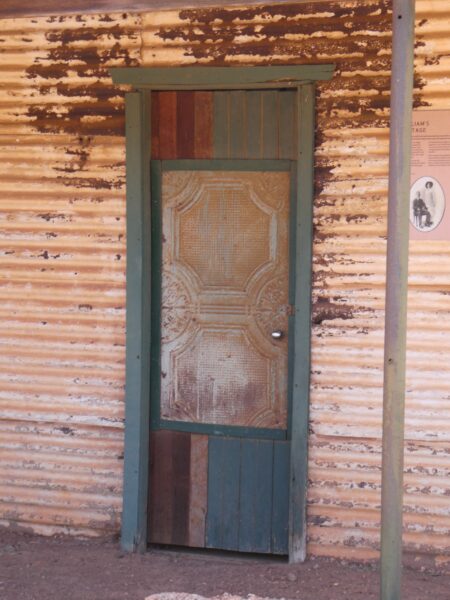

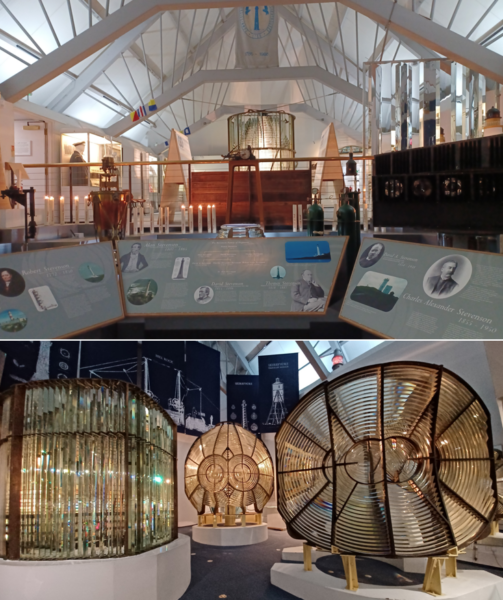

Shoirbhich le muinntir na h-Alba Nuaidh an sin le tuathanas, iasgach, togail bhàtaichean is malairt, fiù ‘s na b’ fheàrr na ann am Baile Anna an toiseach; b‘ ann mar gun do ràinig Tormod agus a threud am Fearann a’ Gheallaidh mu dheireadh thall. Chaochail Tormod ann an 1866, aig aois 85, fhathast athair a pharaiste. Agus ‘s e baile gu math “Albannach” a th’ ann an Waipu gus an latha an-diugh, le cuimhneachain is soidhnichean Gàidhealach is Gàidhlig air feadh an àite, is na Geamaichean Gàidhealach as motha ann an Sealainn Nuadh air an cumail an sin gach Latha na Bliadhn’ Ùire. Tha iad uabhasach moiteil às na tùsan aca, agus tha taigh-tasgaidh anabarrach math ann le sgeul Thormoid agus an sinnsearan, na h-eilthirich fhad-bheatha ghaisgeil seo.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Waipu’s amazing story (2)

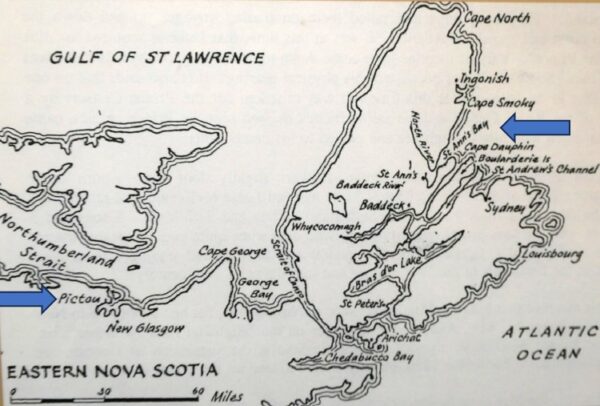

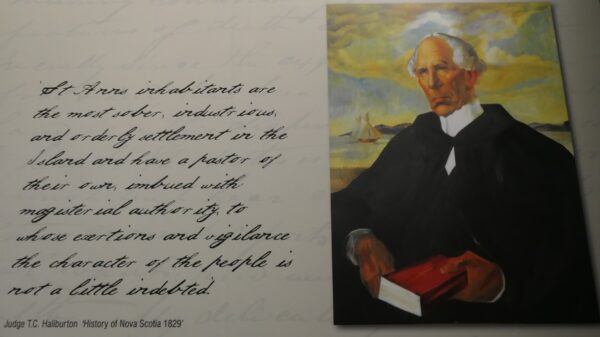

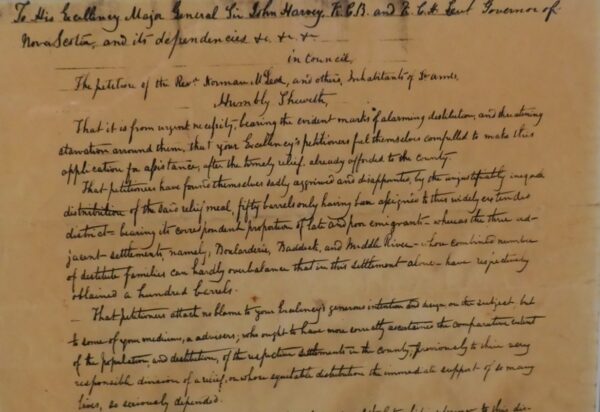

In Part 1 of our story, we left the Rev Norman McLeod pondering emigration again, away from Cape Breton, where life had become increasingly difficult for the settlement with famine on the horizon and the situation in general worsening. But where would they go?

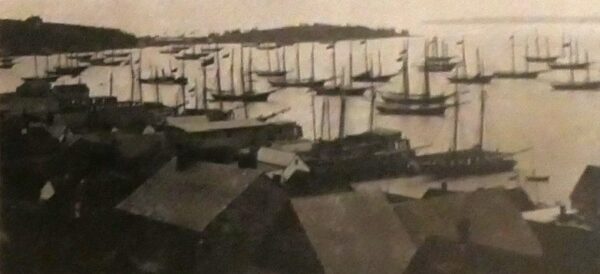

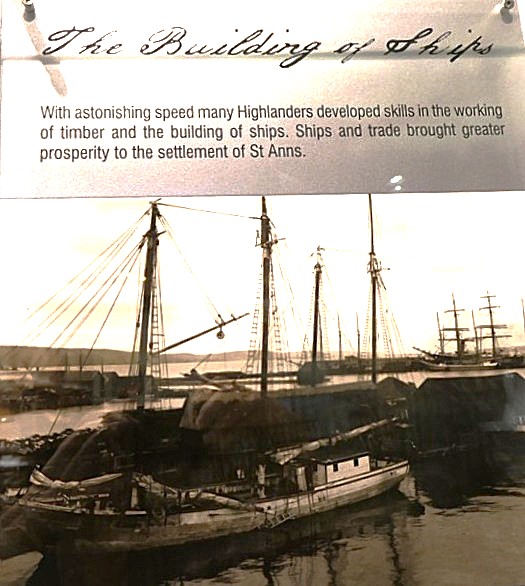

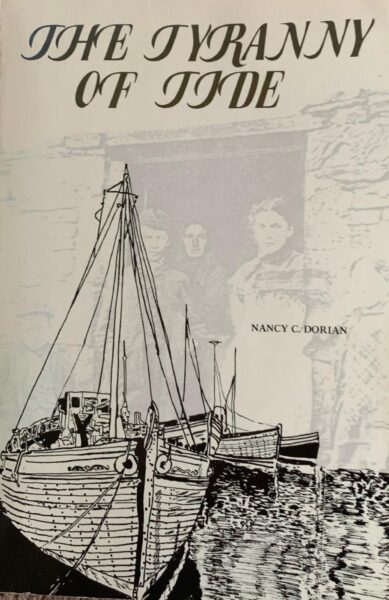

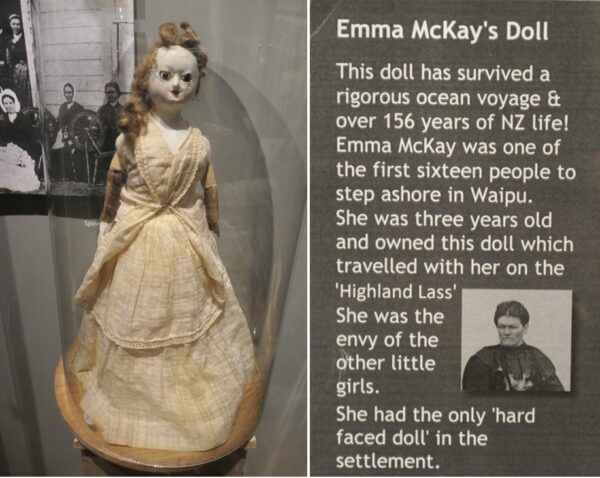

Just at that time, in 1848, a letter arrived from Australia, where Norman’s eldest son Donald had settled, praising the life, land and climate there, and encouraging the family to come over too. That was like a sign to Norman and his faithful flock, and it wasn’t long before they were building a ship which would be suitable for the long voyage – the Margaret, called after Norman’s daughter, and made from timber from his own land. They carried on building further ships too. In October 1851 Norman and the first 135 settlers left St Ann’s, reaching Adelaide in April 1852. The Highland Lass followed them 6 months later. Norman was a good businessman – he sold his land for a good price to finance the voyage, and then got another good price for the Margaret in Sydney, to pay for land and initial subsistence for his family and followers.

But another bitter disappointment was awaiting them – Donald had meanwhile moved to Melbourne, and there wasn’t enough available land for the Cape Breton immigrants to found a settlement in the Adelaide region. So they followed Donald to Melbourne. But in the meantime Australia had been gripped by gold fever, and good land was only to be had for exorbitant prices. They had to live in tent towns along with the thousands who had come in search of gold. Some of the men set off to find work at the “diggings”, as they were short of money. Norman saw that his flock was beginning to break up in an environment of immorality, drunkenness and greed, far worse than in Pictou after their first emigration. And then came something even worse – typhoid. Three of his own sons died within 6 months. He and the majority of the flock decided to leave Australia.

They heard that there was land to be had in New Zealand’s North Island, and since there was no gold there, things would be calmer, and cheaper. Norman wrote to the Governor and they received permission to settle there – and even (unusually) all in one area, so that the community would remain together and be able to speak Gaelic. They sold the Highland Lass and bought the Gazelle. They reached Auckland in 1853, and after various delays and difficulties were permitted to settle in the Waipu area, on land bought by the government from the Maoris, in the north of North Island. Some of the Nova Scotians had stayed in Adelaide or Melbourne, and some in Auckland, where there were many other Gaels, but a sizeable group remained for the new settlement in Waipu from 1854 on.

They sent word to St Ann’s of how suitable this place was, and four other ships came to Waipu from Cape Breton, bringing the numbers up to 900 settlers within a fairly short time. These were the last ships in our story: Gertrude (1856), Spray (1857), Breadalbane (1858) and Ellen Lewis (1860).

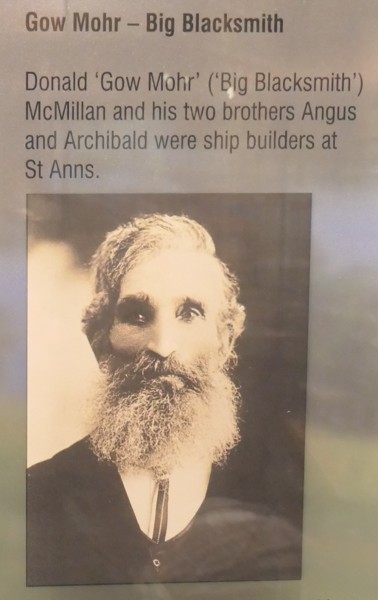

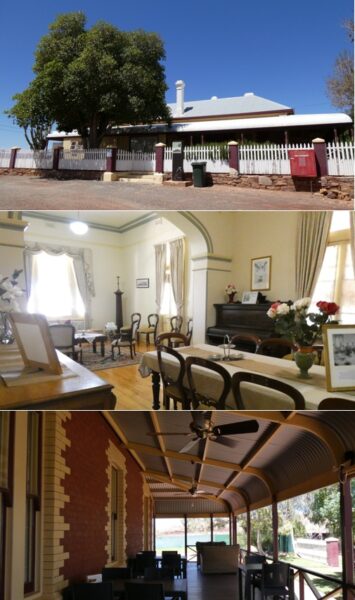

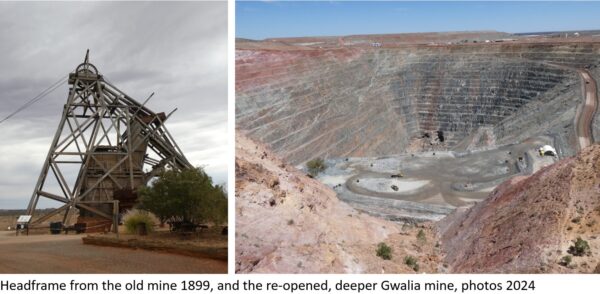

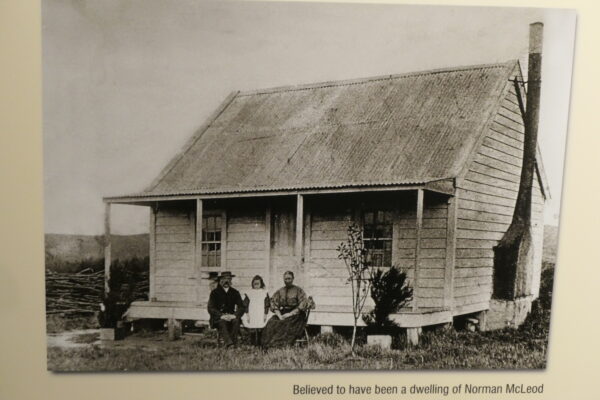

The Nova Scotians prospered there with farming, fishing, boat-building and trade, even more so than they initially did in St Ann’s; it seemed as if Norman and his flock had finally reached their Promised Land. Norman died in 1866, aged 85, still the father of his parish. And Waipu has remained a very “Scottish” town to this day, with Highland and Gaelic memorials and signs, and the biggest Highland Gathering in New Zealand held there every New Year. They’re extremely proud of their roots and there’s an exceptionally good museum there with the story of Norman and their ancestors, those heroic lifelong emigrants.

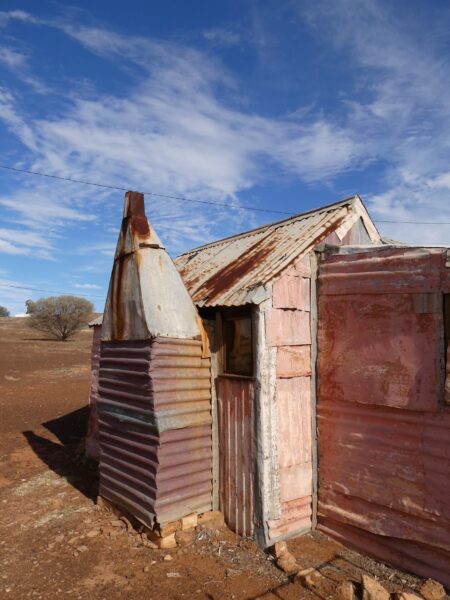

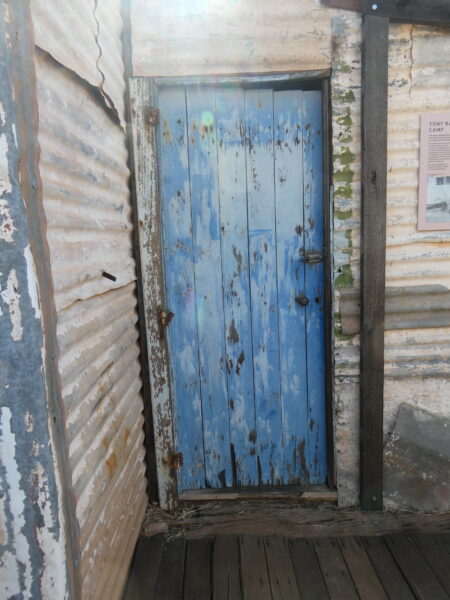

Dealbhan eachdraidheil Taigh-tasgaidh Waipu, le taing. Historic photos Waipu Museum, with thanks.